The world’s top universities are coming to India—can they deliver on the hype?

The institution, with the lush green Aravali hills serving as the backdrop, is the British university’s second offshore campus after Malaysia. Inside, the atmosphere is more collegiate than corporate: students hunched over laptops in cheerful cushioned booths, the hum of a coffee machine, faculty preparing the conference hall for lectures, and prospective students dropping in to inquire about enrolment.

The university opened its doors to the first cohort of 150 students just last month. With induction week wrapped up, the students have bonded over a freshers’ ball, and rolled into employability workshops with industry leaders and alumni mentors. Spread over multiple levels, the campus offers sports and dining facilities within the tech park, with accommodation for residential students a short drive away.

Nearly a thousand kilometres to the west, in Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT City), the emerging business hub near Ahmedabad, Australia’s Deakin University and University of Wollongong, which opened last year, have just welcomed their second cohort of students.

These global institutions establishing branches in the country marks a major shift in India’s higher education. The push comes from the National Education Policy—2020, which aims to internationalise higher education and attract more foreign universities. India’s University Grants Commission (UGC) foreign campus guidelines, a framework to regulate and facilitate their establishment, gave the green signal in 2023.

Under the guidelines, the top 500 universities in global rankings are eligible to establish fully autonomous campuses in India. While they are free to decide admission policies, fee structures, and hiring of faculty, their academic standards, curriculum, pedagogy, assessment and degrees need to be the same as the parent institution, with no franchise or ‘twinning’ (where students complete part of the degree in an Indian university and the rest at a foreign partner university) models permitted.

The initial plan permits 15 such campuses to open in the country. Aside from the universities cited above, the Illinois Institute of Technology, the University of Liverpool, Victoria University, Western Sydney University, and the Istituto Europeo di Design have secured letters of approval and are expected to open campuses within the next two years.

View Full Image

By all accounts, it’s an appealing proposition for students: the opportunity to study on home turf, while enjoying the benefits of an international educational ecosystem. With visa and immigration policies growing more restrictive, studying abroad has become more challenging, prompting many students to seek alternative options.

For foreign universities that have long benefited from Indian student enrolments abroad, the draw is obvious: access to a similar pool of aspiring students, this time, within India’s borders.

“India has a massive youth population and with ambitions of a gross enrolment ratio of 50%, there is a need for capacity within the system,” said David Winstanley, executive director, India implementation, University of Southampton Delhi. “What we bring is another choice, alongside fantastic options that already exist in India.”

The global educational tourism market size was valued at $466.85 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach $1,291.50 billion by 2033, according to IMARC Group estimates. Foreign universities in India are already attracting international interest, with enquiries from students across South Asia and Africa.

The India higher education market size, meanwhile, was valued at ₹5.75 trillion in 2024, according to estimates by the same company. The market is expected to double to ₹11.60 trillion by 2033.

A new chapter

University of Southampton’s campus in Gurugram, which currently offers six undergraduate and postgraduate programmes across finance, computer science and management, with more coming, mirrors the educational approach followed in the UK campus. “It’s a research-active campus, and that research is going to inform the teaching. Our curriculum is ever evolving to make sure it’s relevant, and employability is woven into it, with a focus on skills like creativity, resilience, and agility,” said Winstanley.

View Full Image

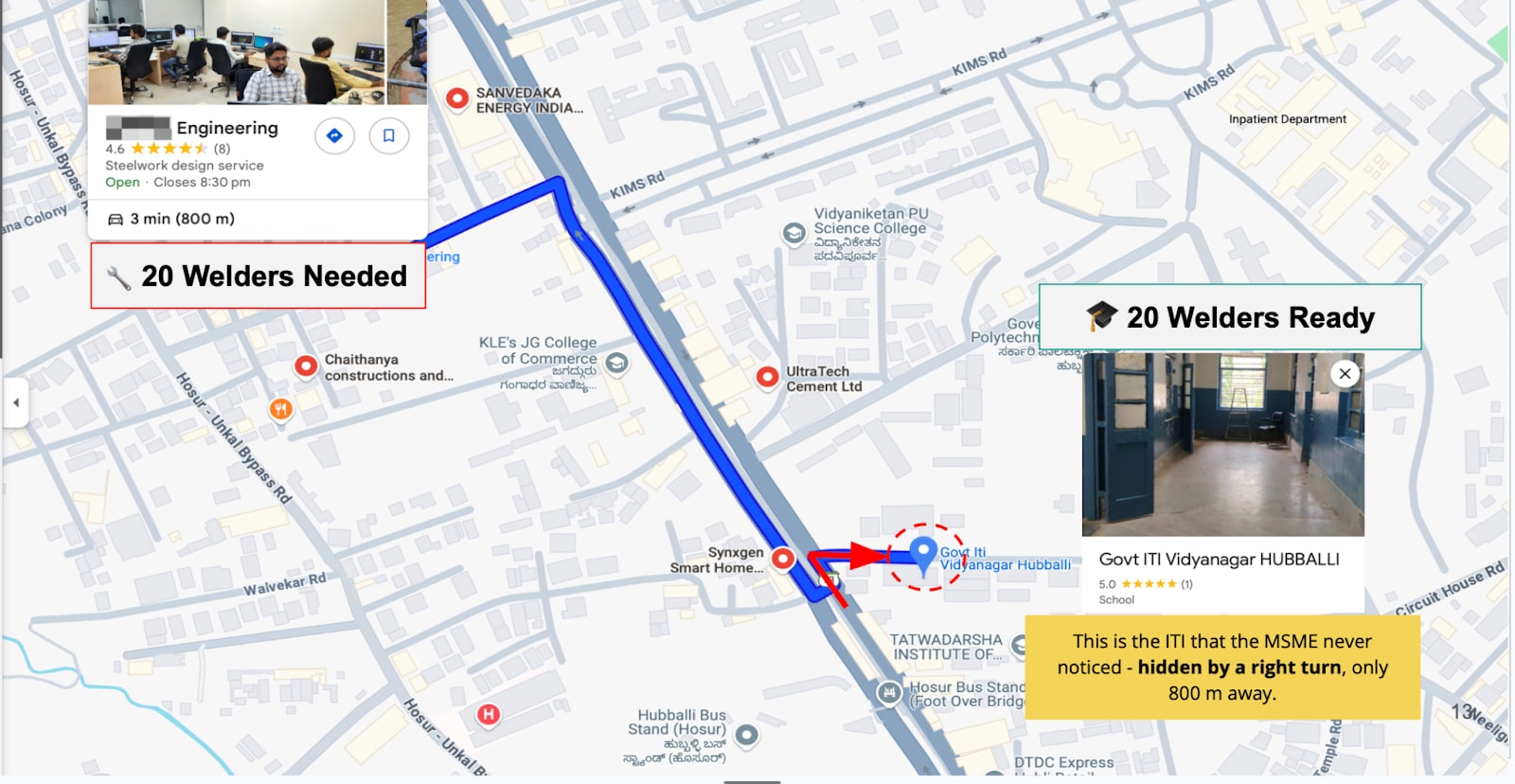

To that end, these campuses are designed to be adaptive and forward-thinking, with state-of-the-art infrastructure similar to their parent institutions. Take, for instance, Deakin University GIFT City, an early mover that opened in July 2024 with two master’s programmes in business analytics and cyber security. Instead of traditional classrooms, it is dotted with collaborative spaces for students and faculty to meet in small groups. Students are enrolled on the basis of CAT exams and interviews.

“What is a two-year course in Australia has been compressed into a 16-month continuous programme with short breaks. The idea is that students can fast-track their journey and then move quickly into industry,” explained Deepak Bajaj, academic and campus director, Deakin University GIFT City Campus.

Drawing in the crowd

The biggest USP of these universities is that they blend global best practices with local opportunities. “We want to give students access to international education without them having to leave home and (to open opportunities) for those who would have otherwise not been able to access Australian quality education,” said University of Wollongong India campus director Nimay Kalyani. The goal is to make international education accessible and flexible, he added.

While the curriculum is aligned with the parent campuses, it has been adapted to the Indian context and work environment. “All the lectures come from Australia and they get curated for the Indian audience,” said Bajaj.

View Full Image

Lectures are tweaked to include discussions on topics such as UPI, which are unique to India, said Hridoy Sankar Dutta, who teaches cyber security at Deakin University, GIFT City. It’s also key for the faculty to be approachable. “Feedback-based assessment, smaller class size and discussion-based learning ensure better outcomes. Our courses focus on fields that have expanded rapidly in the last few years, like cyber security,” he added.

Other attractions for students are scholarships, and immersion and exchange programs, which offer them the chance to visit the parent campuses. The fee structure, ranging between ₹10–16 lakh per year, is roughly one-third to one-half the cost of studying overseas, depending on the university and programme.

“People ask me: will students planning to study at Harvard University or London School of Economics now enroll in the Indian campuses of foreign universities? No,” said Shantanu Rooj, founder and chief executive officer of TeamLease Edtech, a learning solutions company. “Parents who can afford the fees at those colleges will still send their children there. But there are many who can’t afford to. They now have these alternatives.”

The fee structure, ranging between ₹10–16 lakh per year, is roughly one-third to one-half the cost of studying overseas, depending on the university and programme.

Students Mint interviewed across the three campuses felt that credentials from the Indian branches of foreign universities would give them a competitive edge in the job market. “What I like about the course is that it isn’t packed with too many subjects, like in Indian colleges. With three lectures a day, I have time to work on assignments,” said Krinali Shah, 25, from Ahmedabad, who studies business analytics at Deakin GIFT City.

Her batchmate, Vedant Borle, 26, from Pune, finds the interactive and industry-oriented teaching style transformative. “It’s a refreshing change from the traditional classroom format. We collaborate with peers from diverse backgrounds and get to work on real projects with clients from Australia, who give us feedback. That experience completely changed the way I think,” he said.

Some students said the curriculum design helped them understand local issues in a broader context. “For example, in a module on regulation and ethics, we study both Australian and Indian laws, which helps connect the dots. We have industry visits on campus every week, and as part of a smaller cohort, it’s easier to connect with them,” said Cerin Elsa Joji, 24, who is studying FinTech at University of Wollongong GIFT City.

View Full Image

Foreign universities coming in now can catalyse and accelerate the quality of education in the country, said Ramkumar Ramamoorthy, former chairman and managing director of Cognizant India, and former pro vice-chancellor, Krea University. The universities can bring in best practices in pedagogy, innovative teaching methods and academia-industry linkages, with their alumni supporting them in a big way.

“They can encourage joint research across global institutions, with cutting-edge infrastructure, especially in newer areas such as AI, biotechnology, semiconductors, renewable energy, and aerospace. They can also be a platform for exceptional business case studies from India to be incorporated into the global curricula,” he added.

Filling the gap

These campuses have come up during a period of churn in India’s higher education ecosystem, with several progressive institutions making a mark in the last decade.

“If we step back and look at the challenges in Indian higher education, governance has been over-centralized with an affiliating system, which gives little autonomy to institutions. Added to that, there has been a deep disconnect between academia and industry,” said Ramamoorthy. “While the affiliating system had a role to play when we needed to standardize quality education, we now need to move to a Tesla model of education and drive innovation with agility,” he added.

We now need to move to a Tesla model of education and drive innovation with agility.

— Ramkumar Ramamoorthy

The newer crop of private institutions backed by Indian corporate houses that came in to fill that gap—universities such as Shiv Nadar, Azim Premji, Mahindra, Ashoka, Krea, and Nayanta—drive world-class education by attracting top faculty, embracing interwoven and immersive learning, and building strong industry connections. At Ahmedabad University, for example, the effort has been to build an interdisciplinary institution, said Pankaj Chandra, the vice-chancellor.

All this is playing out at a time when concerns over the employability of Indian graduates are growing, and being echoed by industry and government leaders. The India Skills Report 2024, published by Wheebox Talent Assessments, in collaboration with the All India Council for Technical Education, the Confederation of Indian Industry, and the Association of Indian Universities, shows only 50% of graduates as employable.

Industry experts believe foreign campuses could improve the overall quality of education, raising professionalism and employability. Tier II and III colleges would now have to raise their game.

Curiosity among corporates is growing as well, especially since these campuses are housed within business hubs. Students, too, are eager for big recruiters to step in as placements get underway. Some efforts are already paying off—the National Australia Bank, for instance, hired seven graduates from Deakin’s first cohort in India.

‘The jury’s still out’

While foreign universities say they bring in globally relevant education, in areas spanning science, technology, business and entrepreneurship, and also boast of a diverse faculty with international teaching experience, many industry watchers remain sceptical about the benefits coming to India.

“The jury’s still out. We will have to see what they actually deliver. Many universities are heavily dependent on international student financing, so we should be clear that’s the intent,” said Pankaj Chandra. “They are offering market-driven courses. If they are able to bring the ecosystem, culture and faculty from their home campuses, then they can become valuable and add to the institutional strength in India,” he added, saying that if they are simply teaching schools, they will be just like any other private institute.

Given the high fee structure, there is a risk of inequalities widening, as is already happening with the newer set of private Indian universities.

Given the high fee structure, there is a risk of inequalities widening, as is already happening with the newer set of private Indian universities, warned Ramamoorthy. But, he said, it will be important to provide scholarships at scale to uphold India’s social justice goals.

Some experts also believe this market will remain niche unless the campuses offer clear pathways to work abroad. Prabakaran Srinivasan, an education advisor, said that while the turbulence in visa and immigration policies has prompted students to look at wider options, they also wonder whether enrolling in a foreign campus in India will deliver returns on their investment. “Students ask if it will help them get an internship or job abroad. If the advantage is only an international curriculum, they could access that online. The truth is, students want to enroll at a foreign university not just for the knowledge but for the experience of living in that country,” he said.