How one Indian district is keeping graduates closer to home

Outside, the late monsoon heat clung to the air; inside, a brass gong punctuated each speaker’s turn at the microphone.

One official began with pride. Hubballi-Dharwad, he said, had always been more than just a twin city: an educational capital, a cultural centre, a trading hub. “If this experiment succeeds anywhere, it should be here,” he told the room.

But almost immediately, the conversation turned to harder truths. “Every year nearly 70,000 students pass out of Karnataka’s ITIs,” said Ragapriya R., the commissioner of industrial training. “But how many actually fit what industry needs? How many stay in jobs instead of drifting into gig work?”

From the back benches, placement officers rose to add their frustrations. “Our students want jobs only within 15 or 20 km of home, even if Honda or Toyota offer them more,” said Shivaprakash V. Chitragar, principal of ITI Vidyanagar, Hubballi-Dharwad, recalling how his trainees refused to migrate outside Hubballi-Dharwad. Another spoke of the mismatch between industry expectations—“10 hours, 12 hours of duty”—and what trainees were willing, or sometimes able, to take on.

One speaker reached for a metaphor. Divya Prabhu G.R.J., the district commissioner of Dharwad, compared the process of matching employer and employee to a matrimonial site. “Earlier, matches were made by word of mouth. Today you browse filters—slim, tall, fair. But does that guarantee compatibility? No. It takes deeper understanding.” So too with jobs, she argued—mere postings and résumés were not enough.

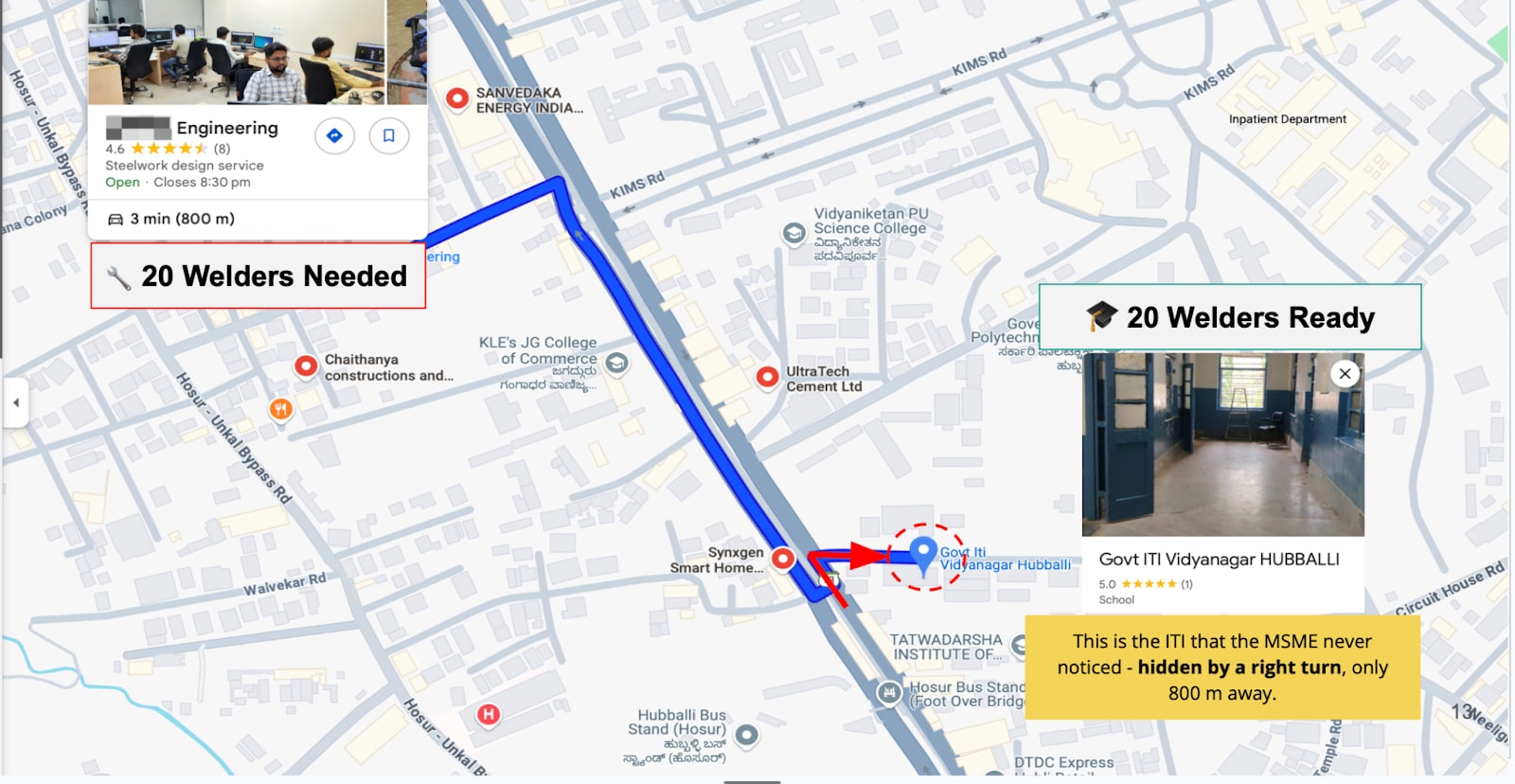

Then came the bluntest example of all. “There is an ITI on one side of the road and an MSME on the other—and they have never met,” said another speaker, shaking his head. “The students inside don’t know the jobs exist; the employer across the road never walks in. Both are invisible to each other.”

View Full Image

For decades, ITIs have been the backbone of India’s skilling system: government and private institutes where students, mostly from low-income families, train in trades like welding, carpentry, and electrical fitting. In theory, they are the bridge to steady work. In practice, placements remain poor—often below 30%—and employers have long criticised the gap between classroom training and shop-floor needs.

The gathering in Dharwad was not just another official conclave. It marked the debut of a new experiment in one of India’s hardest problems: connecting its hundreds of millions of young people with work that is local.

The premise is simple to describe and hard to execute: What if jobs, candidates, and benefits could appear on a digital map, in an app? The way restaurants or petrol pumps do? A ‘blue dot’ on a screen, signalling not just where something is but also intent: who I am, what I have, what I want.

It is the missing piece in a country that has already built population-scale digital rails for identity (Aadhaar), payments (UPI), and credentials (DigiLocker). Yet, until this year, said district skill officer Ravindra P. Dyaberi, his department relied on “conventional job fairs, offline banners, posters.” Students drifted into gig work or back to family farms. Employers wasted weeks chasing leads that evaporated.

The Blue Dot project, piloted first across Dharwad’s ITIs and its ring of MSMEs, does something different: profiles are captured by a voice bot, verified by principals and placement officers, made visible over an open protocol, and matched to nearby jobs in real time.

Whether this model can scale—or whether it will stumble like past skilling schemes—is what drew so many voices into that hot, crowded hall.

Who built the rails

The idea of Blue Dots and the reference app came from EkStep Foundation, cofounded by Nandan Nilekani, Rohini Nilekani and Shankar Maruwada. The foundation also funded and published its protocol (called ONEST) and credential issuance/verification as digital public goods (DPGs). The DPGs are free for governments, nonprofits and private players to use—each participant can invest in their own operations and configuration to run a district pilot.

View Full Image

In Dharwad, these DPGs are used by the Karnataka Skill Development Authority, the department of industrial training & employment and the district administration. Internally, their effort is nicknamed “painting the town blue.”

Head Held High, a nonprofit, supports the fieldwork. Local groups—Deshpande Foundation, Unnati Foundation, and Gigin—are use the same rails to match local youth to local jobs.

Nandan Nilekani, the chairman of IT services major Infosys, and the founding chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India, is also EkStep’s chair. He is cited as an “inspiration and guide”, but not the originator of the idea.

How the pilot took shape

The first seeds of the project were planted in March 2025, when two representatives from the EkStep Foundation walked into the government ITI in Dharwad with what sounded like an improbable proposal: build a digital map of jobs and job-seekers.

Ravindra P. Dyaberi, the district skill development officer of Dharwad and principal of the ITI, remembers his skepticism. “How can this be a digital platform?” he asked.

After hours of discussion, he conceded.

That week, an industry association set a Saturday 4 p.m. meet in Hubballi so MSMEs could see the system together. “Two or three agreed, then more followed,” said Suresh Kumar S. Jalwad, the placement officer at ITI Dharwad.

View Full Image

The team dropped the Android Package Kit (APK)—the format used by the Android operating system to install mobile applications—and shifted MSMEs to a web portal/phone onboarding, addressing device and data fears.

The first pilot was modest. Five SMEs and about a hundred students were ‘blue-dotted’ at ITI Dharwad. Profiles were captured through an AI-powered bot in the app that asked in Kannada or Hindi: ‘What is your trade?’ ‘Where are you willing to work?’ ‘What salary do you expect?’

Within weeks, the first placement drive was held. Ten to 15 companies turned up, 50 students participated, and nearly 200 interviews were conducted, all tracked through DigiPass, a quick verification token.

On the ground, the work was painstaking. Volunteers from other non-profits, like Atiya Yasmeen of Head Held High Foundation, came in from Raichur and Kalaburagi (formerly Gulbarga) to fan out across Dharwad. They went door to door, persuading small businesses to try the app. Yasmeen, who had once gone door to door herself, in Raichur, looking for work after her father’s death, knew the stakes. “In Raichur, we have jobs. But local students don’t even know where to find them,” she said.

Some MSMEs were sceptical. “Go away, you’ll put penalties on us later, asking how many labourers we have, whether we are paying tax”, one company told Yasmeen.

View Full Image

Convincing them required backup. Placement officers accompanied her, vouching for the project’s legitimacy. Industry associations were brought in to ease the mistrust.

Meanwhile, the AI bot itself was learning in real time. Students remembered the glitches. “It kept saying, ‘Sorry ma’am, sorry ma’am,’ when one girl told her name,” a trainee laughed. Teachers had to prod from behind: Speak loudly, don’t be afraid, it’s only a bot. Calls sometimes dropped halfway.

To cope, the team instituted nightly field escalation calls. “We listed what went right, what went wrong—the bot mishearing names, questions confusing students, industries asking us to change the APK,” Yasmeen said. “Next day those fixes would go in.”

The approach was not limited to Dharwad. In Vellore, Tamil Nadu, a role-bot was deployed at the Darling Residency hotel to screen applicants for housekeeping and front-desk roles. The bot asked questions in Tamil, recorded answers, and sent summaries to the HR desk. “It was the first time we could pre-screen in the local language without staff sitting through 50 interviews,” the manager said.

By the summer, 350 MSMEs and over 1,100 students had been blue-dotted across Dharwad district. Job-seekers were receiving interview calls even before completing their training. Some MSMEs made their first ever digital hires.

At ITI Dharwad, Dyaberi and his team organized the first placement drive using the new system. 10 to 15 industries and 50 students participated. Nearly 200 interviews were conducted in a single day through DigiPass. For the first time, employers could see verified skills on their screens before meeting a candidate.

View Full Image

For Suresh Kumar, a placement officer at Government ITI Dharwad, the change was jarring.

“Before the Blue Dot, it took me at least a week or 15 days to organize a placement,” he recalled. “We had to visit the industries, collect their requirements, call back our trainees—even those who had passed out years earlier—and then arrange a campus interview or a mela. If it was a bigger event, I had to prepare the whole ITI. It felt like a wedding—with none of the guarantees.”

Now, the bot did the first round of questions, and within hours, the shortlist appeared.

“Five of our trainees were given letters even before completing training,” he added.

Jobs were once announced on scraps of paper pinned to trees—“Female wanted, accountant, ₹20,000 per month”. Or in tiny newspaper ads, or as notices pasted on workshop gates. Word of mouth carried some, rumours the rest. For the first time, the interviews were being logged, verified, and matched in real time by the system.

The multiplier effect

If the idea of a blue dot felt abstract in policy rooms, its weight was sharpest in the voices of those who lived the gap.

In Dharwad, students like Bushra Kotwal and Farhad Anjum from local ITIs no longer wait months to hear of openings. “Earlier, it could take three or four months,” one said. Their sewing and embroidery profiles were created in minutes, verified by their principal, and made visible on a map that showed jobs within reach of their homes in Murgamata, near the railway station.

View Full Image

“I want a job in Hubballi-Dharwad only,” said one of Shivprakash’s trainees, even after being shortlisted by Toyota and Bharat Electronics.

Others described why proximity mattered.

“Time is saved. I can spend more with my family, and my parents don’t worry if I am nearby,” said Anjum, a trainee at Vikas ITI in Hubballi. She explained how her uncles working in cities carried the strain of long commutes and separations. “That’s why local jobs matter,” she added.

For MSMEs, the frustration was just as visceral.

“If a worker comes from far away, he will try for two or three months, then leave. If I hire someone from nearby, even if I pay ₹ 5,000 less, he will stay,” an industrialist said.

MSMEs typically spend about ₹1,000 per hire and wait weeks to fill roles. On the Blue Dot rails, time and cost fall to roughly one-tenth, they said. Every week saved means fewer delays, less subcontracting, and more output.

For job seekers, a digital résumé (over 80% lacked one) and a map of nearby jobs means access and choice. Keeping work local also circulates money in the region—on transport, housing, food and services—creating a multiplier effect in the district economy.

View Full Image

Why now, why here

The choice of Dharwad as the launchpad was not accidental. The twin cities of Hubballi-Dharwad have long called themselves Karnataka’s “second capital”—home to universities, engineering colleges, ITIs, and a restless youth population. But industrial growth has never kept pace with its intellectual reputation.

Dharwad’s paradox: The district has over 3,100 MSMEs, generating 8,000–10,000 fresher openings a year. About 2,000 students pass out if ITIs annually. And yet, MSMEs report shortages, while placement rates for youth remain south of 25–30%. The gap isn’t supply or demand. It’s visibility and trust.

“Even though we are called Karnataka’s second capital, this region never got the parent industries,” said Ramesh Patil, who runs Patil Electric Works, a 120-employee firm that supplies components to Bosch and Tata Motors.

Instead, Dharwad’s factories were left to survive as feeder units. “We are surrounded by hundreds of MSMEs that supply components,” Patil added, “but the anchor industries that could have changed this region’s trajectory never came.”

Girish Nalwadi, president of the North Karnataka Small Scale Industry Association, pointed out that the state’s heavyweights—BEL, BHEL, BEML—had their large units elsewhere. “BEL has got 12 manufacturing units across the country,” he said. “There is nothing in north Karnataka.”

That absence of anchors produced another paradox. North Karnataka exported labour to the south, even as its own factories remained starved of workers.

View Full Image

Looking ahead

Each evening, the field team still gathers for a 10-minute call. The notes are repetitive but vital: a bot misheard a name in Kannada, a prompt confused a student, a call dropped mid-answer. The fixes are pushed the next day—a loop of trial and correction that keeps the system alive.

The same rails now carry other value. In Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan, a scholarship that once took six months and 50 steps cleared in two minutes when DigiPass credentials were used. Profiles that had never appeared in any ledger were suddenly findable.

The analogy is familiar in India: just as UPI made payments flow because everyone shared the same rails, work starts to move when jobs and profiles ride the same pipes.

The district model is being extended by KSDA across the Belgaum division, with other Karnataka districts to follow. Mysuru will test digital job fairs. Uttar Pradesh is starting a similar district pilot.

View Full Image

“We wanted technology to bring together job seekers and job providers. After reviewing the pilot with students, industry, and district officials, we’d like to scale it,” said V. Ramana Reddy, chair of KSDA.

On the benefits side, after Jhunjhunu, the same approach was run in Patna and Haridwar with the Piramal Foundation, the department of empowerment of persons with disabilities (DEPwD), and the Artificial Limbs Manufacturing Corporation of India. It is now being piloted at a larger scale in Ranchi. Separately, edtech company Physics Wallah is expanding a pilot to convert more students from economically weaker sections into ‘blue dots’ and surface needs to funders.

The last word does remain with the human stakes. At Government ITI Mummigatti, volunteer Atiya Yasmeen recalled one boy’s quiet relief when he realized he could work close by and still care for his widowed mother. “That was his happiness,” she said. For him, the blue dot was not just a signal on a screen, but one less bus fare, one less rumour to chase, one more hour at home. For policymakers, it may be infrastructure. For Dharwad’s students, it is recognition. Seen by employers across the road, seen by a system that had long missed them, seen—finally—in the demographic dividend India has spoken of for decades.